By Michael Andrews

•

February 20, 2025

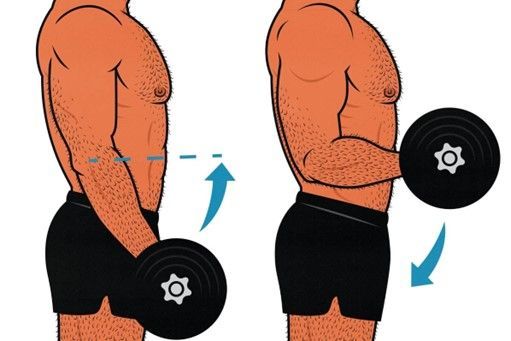

The Role of Load Management in Rehabilitation: A Framework for Returning to Function, and Injury Prevention. Load management is often associated with high performance sport, but its principles are just as critical in rehabilitation. Whether guiding injured workers back to work, older adults to independent living, or patients recovering from injuries, progressively and systematically managing load is essential for recovery, injury prevention, and long-term function. A major challenge in rehabilitation is balancing workload progression to optimise adaptation without overloading healing tissues. Sudden spikes in training load or returning to full activity too soon significantly increase the risk of re-injury. Exercise physiologists can use load monitoring, periodisation, and predictive planning to ensure a structured and safe return to work, life, or recreational activity. Understanding Load and How to Monitor It In rehabilitation, load refers to the total amount of mechanical and physiological stress placed on the body. This includes external load; the measurable work performed (e.g., weight lifted, steps taken, distance covered, time spent in physical activity), and internal load; the body’s physiological and perceptual response to that work (e.g., heart rate, rate of perceived exertion (RPE), pain, fatigue). Both external and internal load must be monitored to ensure that rehabilitation is progressive yet not excessive. One of the most useful frameworks for load management is the Acute: Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR), which helps determine whether a patient is progressing at a safe rate or at risk of overload. A sudden spike in acute load (ACWR >1.5) increases injury risk by 2-4 times in the following week. Therefore, a gradual increase in chronic load (≤10% per week) is essential to build resilience and capacity. - Acute Load = The total workload over the past week. - Chronic Load = The rolling 4-week average of workload. - ACWR = Acute Load ÷ Chronic Load. Patients often underestimate how small spikes in activity (e.g., resuming full work shifts after time off, or inconsistent engagement in their self-management plan) can lead to flare-ups or re-injury, and by tracking ACWR, we can educate the patient accordingly and prevent excessive acute spikes while ensuring a steady increase in chronic workload, reducing the likelihood of setbacks and ensuring a progressive return to function. To apply these principles effectively, we need accurate and practical ways to measure and track load in real world rehabilitation settings. Unlike athletic settings, maximal strength testing (1RM) is often inappropriate in rehabilitation. Alternative methods include volume-based and time-based load tracking, perceived exertion and fatigue monitoring, and functional testing. - Monitoring total weight lifted per session (sets × reps × resistance). - Measuring time under tension for endurance-based activities. - Using exercise RPE and session RPE to gauge effort. - Reassessing movement capacity, endurance, and strength progression over time. Using subjective feedback alongside objective load tracking allows for better exercise prescription and progression. Asking the right questions can guide real-time modifications: External Load Questions: - How much activity did you complete this week? - How does this compare to last week? - Did you struggle with any tasks or exercises? Internal Load Questions: - How fatigued do you feel after sessions? - How long does it take you to recover? - Are you experiencing pain or discomfort, and how does it change with activity? Structuring Load Progression for Long-Term Success Periodisation is the planned progression of training load over time, ensuring continued adaptation without excessive strain. While typically used in athletic settings, structured periodisation is just as valuable in rehabilitation, helping prevent stagnation by adjusting workload over time, ensuring progressive overload while respecting tissue healing and recovery rates, and guiding return-to-work planning by matching rehabilitation loads with real-world demands. A structured approach allows us to compare a patient’s current workload tolerance to their end goal and reverse-engineer a safe progression plan. If a patient needs to tolerate X hours of work or Y level of activity, we can use their current capacity and reverse-calculate a safe, gradual progression timeline and by maintaining consistent, small increases in chronic workload, we minimise setbacks and ensure safe long-term recovery. Linear Periodisation is best suited for straightforward recovery cases with minimal variability in symptoms. While, nonlinear periodisation may be more practical for rehabilitation, as symptoms and capacity can vary day-to-day. - Linear Periodisation: Steady, predictable increases in intensity, volume, or duration over time. - Nonlinear (Undulating) Periodisation: Load fluctuates based on recovery, pain, and function. Applying Periodisation to Rehabilitation Planning Step 1: Establish a Baseline Identify current weekly workload (e.g., hours of tolerated activity, steps, resistance training volume) and functional deficits (e.g., strength, endurance, movement capacity). Step 2: Define the End Goal What workload is required to return to work, sport, or daily function? This could mean sustaining an 8-hour work shift, lifting a certain weight, or tolerating daily activities without pain. Step 3: Plan a Safe Progression Gradually increase chronic workload by ≤10% per week. Avoiding acute spikes (ACWR >1.5) to prevent setbacks. Monitor pain, fatigue, and function to guide daily and weekly adjustments. By integrating load monitoring, periodisation, and predictive planning, exercise physiologists can create safe, structured rehabilitation programs that optimise recovery, prevent re-injury, and guide patients back to work, sport, or daily life with confidence. Key Takeaways for Exercise Physiologists - Load management is essential in rehabilitation, not just in sports. - Acute vs. chronic load balance is key. Avoiding acute spikes prevents injury, while gradual increases build resilience. - Tracking external and internal load ensures a data-driven approach to exercise prescription. - Periodisation structures rehabilitation progression, ensuring steady gains without excessive strain. - Patient education on workload progression improves compliance and reduces re-injury risk. References Impellizzeri, F. M., Menaspà, P., Coutts, A. J., Kalkhoven, J., & Menaspà, M. J. (2020). Training load and its role in injury prevention, part I: back to the future. Journal of athletic training, 55(9), 885-892. Gabbett, T. J., Kennelly, S., Sheehan, J., Hawkins, R., Milsom, J., King, E., ... & Ekstrand, J. (2016). If overuse injury is a ‘training load error’, should undertraining be viewed the same way?. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(17), 1017-1018. Windt, J., & Gabbett, T. J. (2017). How do training and competition workloads relate to injury? The workload—injury aetiology model. British journal of sports medicine, 51(5), 428-435. Jildeh, T. R. (2024). Editorial commentary: load management is essential to prevent season-ending injuries in the National Basketball Association. Arthroscopy, 40(9), 2474-2476. Bache-Mathiesen, L. K., Andersen, T. E., Dalen-Lorentsen, T., Tabben, M., Chamari, K., Clarsen, B., & Fagerland, M. W. (2023). A new statistical approach to training load and injury risk: separating the acute from the chronic load. Biology of sport, 41(1), 119-134. Williams, S., West, S., Cross, M. J., & Stokes, K. A. (2017). Better way to determine the acute: chronic workload ratio?. British journal of sports medicine, 51(3), 209-210. Carey, D. L., Ong, K., Whiteley, R., Crossley, K. M., Crow, J., & Morris, M. E. (2018). Predictive modelling of training loads and injury in Australian football. International Journal of Computer Science in Sport, 17(1), 49-66. Impellizzeri, F. M., Shrier, I., McLaren, S. J., Coutts, A. J., McCall, A., Slattery, K., ... & Kalkhoven, J. T. (2023). Understanding training load as exposure and dose. Sports Medicine, 53(9), 1667-1679. Lorenz, D. S., Reiman, M. P., & Walker, J. C. (2010). Periodization: current review and suggested implementation for athletic rehabilitation. Sports Health, 2(6), 509-518. April Hawser Exercise Physiologist Exercise Rehabilitation Services – NSW